The way in which Detroit’s face surveillance system is set up poses risks that may not be adequately mitigated by the existing policy that governs its use. The policy recognizes some of the risks that face recognition technology poses. The policy states, for example, that officers and agencies using the system:

“…will not violate First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendments and will not perform or request face recognition searches about individuals or organizations based solely on their religious, political, or social views or activities; their participation in particular noncriminal organization or lawful event; or their races, ethnicities, citizenship, places of origin, ages, disabilities, genders, gender identities, sexual orientations, or other classification protected by law."

However, because of its pairing with Project Green Light, DPD’s face surveillance system runs the risk of doing just that.

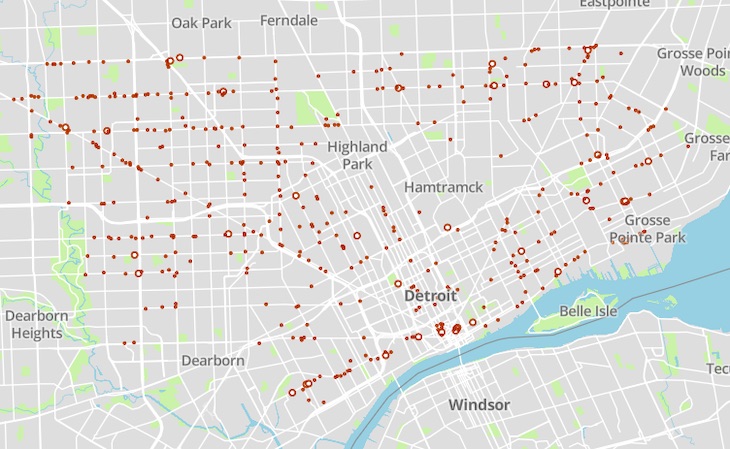

Project Green Light Partners are still predominantly gas stations, liquor stores, and other late-night businesses. But an increasing number of community centers and support services are also part of the city’s growing camera network. As of April 2019, Project Green Light partners included 11 churches, 12 stand-alone pharmacies, eight schools, and at least 15 clinics—providing addiction treatment, reproductive health and family planning services, counseling, and youth-specific care to Detroit’s residents. More than 30 residential locations—including apartment buildings, senior living centers, and hotels are also current partners. Other churches, schools, and support centers are not part of Project Green Light but are immediately adjacent to partner businesses and potentially within range of their neighbors’ cameras.

Figure 4: Wolverine Human Services, an organization that provides residential treatment for children, substance abuse care, foster and adoption services, and other programs directed towards vulnerable children, became a Project Green Light Partner in November 2017. (Source: Google, all rights reserved.)

Attending many of these locations reveals deeply personal information about a resident’s “religious, political, or social views or activities” or “participation in particular noncriminal organization or lawful event. While these activities may occur in public, most of us do not expect to be sharing our attendance at a church service or an addiction treatment center with law enforcement. We do not have to be hiding illegal activity to desire privacy in a choice to worship, seek counseling or treatment, or obtain an abortion or other medical service.

Without restrictions on where face surveillance is deployed, the Project Green Light system may inadvertently violate the very policy established to protect residents against its potential harms. The goal of these surveillance cameras is to make Detroit’s residents feel safe going about their daily lives. Adding face surveillance to these cameras risks doing the opposite.